“Mad, bad and dangerous to know” sounds like a promise to a young Cambridge student in need of an article for the University’s art magazine. From 1963 until Francis Bacon’s death in 1992, Michael Peppiatt was a dependable companion and intimate observer of the artist’s turmoil and genius.

“Francis Bacon in your blood” is the most exhilarating book about an artist one could read. Peppiatt’s beautiful prose generously affords us a rare and privileged glimpse into Bacon’s brilliant and complicated mind. Vividly describing the creative process, whose motives are equally simple and sophisticated, Peppiatt takes us through his journey of love, admiration and understanding, like no one before him.

Through colorful accounts of endless nights of prodigious drinking, we discover an endearing figure, a sort of romantic idea of an artist, from raging Bull-Terrier to munificent friend, relishing life, with the good, the bad, and the ugly. (The sublime, the queer, and the truly vile.)

Bacon was in turn generous or brutal, charming or vitriolic, pontifical or in the throes of self-loathing, but never, ever dull. His “nostalgie de la boue”, defined by Merriam-Webster as yearning for the mud, attraction to what is unworthy, crude, or degrading, is a seminal aspect of his character.

“I like unmade beds, but I like them unmade by love.” And here is the key word: Love. But Bacon’s idea of love is a form of sadistic expiation. An unworthy Irishman atoning for his sins of lust and success. Love, as life, can only be short and brutal; there can be no happiness, only yearning, suffering and death. A masterful colourist, his paintings reflect his disquietude. In Francis’s own words:

” As you know I myself terribly want to avoid telling a story. I only want the sensation. What I long to do is to undercut all the anecdotes of storytelling yet make an image filled with implications. I have always believed that great art comes out of reinventing and concentrating what’s called fact, what we know of our existence – a reconcentration that tears away the veils that fact, or truth if you like, acquires over time. “

Or, in Peppiatt’s thrilling description when, in 1968, he discovers Bacon’s recent work at Marlborough Gallery:

“…twisted bodies rise to the surface of the glass like corpses in water, disfigured, discolored, and stay there. Once you have seen them, there is no getting away, no exit. Each of the figures is held at some extremity of pain, of guilt, of fear, of lust or all combined, it’s never clear.…There are screams issuing from wide-open mouths, but they are muffled, even soundless, because there is no space for screams to be heard and the bodies are pushed up, almost flattened, against the glass, and left there to gasp.

…There is no air for fear to scream or lust to pant, like the new degree of torment invented by a subtle medieval divine. Contours deliquesce, limbs buckle, and the head is reduced to a mere stump of misery. Trying to counter the great waves of threat that I feel breaking over me I get up from my stool and go up to look at them close to, following the great swirls of pigment as if they might lead me to the source of so much pain. But the infinitely pliant, grainy paint only reveals further sadomasochistic refinement and humiliation. No facial feature has resisted the onslaught. Eyes are put out and noses splayed as a matter of course. Whole faces are flayed to a pulp around chattering teeth, while black and green spots bloom on the pink skin like a terminal disease.”

…”The range and inventiveness in tearing and flaying human shapes is overwhelming. Heads and bodies tumble out in ever-greater extremity, ever-greater virtuosity, on to the picture plane. All the forms in this high wire act are taken to the brink of abstraction. But they don’t topple over, they are brought to the edge and held in check, a hair’s breath from dissolving into formless, painterly chaos. And this seems to me the key: the balance is maintained by the vitality that courses beneath. Under this raging destruction the blood runs so ruddely, as if in defiance, and thick white flares of sperm lace the mutilated body parts together. Are these things essentially about sex? …Far from an anguished record of our brutal times, from death camp to nuclear bomb, are the flailings and gougings, the twisted limbs and half-obliterated heads a kind of paean to the further reaches of sadomasochistic coupling? Is this an extended love song?”

© Michael Peppiatt “Francis Bacon in your blood” Bloomsbury Circus, London, 2015

Images @ Estate of Francis Bacon

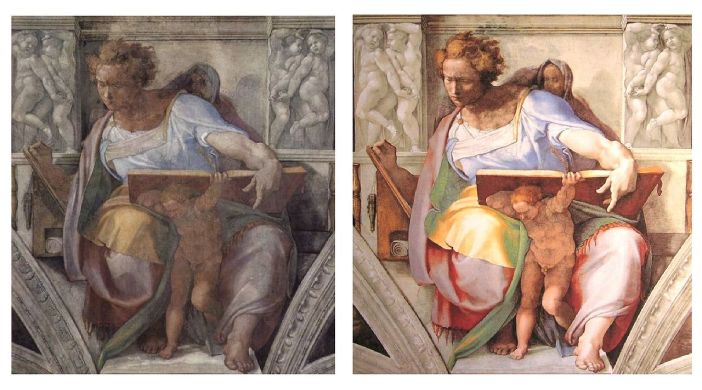

One of our Professors at University, Gianluigi Colalucci was head restorer for the Sistine chapel project. Close examination by his team revealed that apart from smoky deposits, seepage deposits and structural cracks; the thin “pictorial skin” of Michelangelo’s frescoes was in excellent condition. Most of the paint was well adhered and required little retouching. The plaster, or

One of our Professors at University, Gianluigi Colalucci was head restorer for the Sistine chapel project. Close examination by his team revealed that apart from smoky deposits, seepage deposits and structural cracks; the thin “pictorial skin” of Michelangelo’s frescoes was in excellent condition. Most of the paint was well adhered and required little retouching. The plaster, or