“It’s like a nervous system. It’s not described, it’s happening. The feeling is going on with the task. The line is the feeling, from a soft thing, a dreamy thing, to something hard, something arid, something lonely, something ending, something beginning.”

Born in Lexington, Virginia in 1928, albeit to parents from Massachusetts and Maine, Twombly embraces his southern upbringing with gourmandise. “The traditional elements that thickened the “atmosphere” of Southern life – a honeyed ease with spoken language and a rich literary tradition, a certain sensual languor, and the lingering romance of fallen grandeur” *1

With Kurt Schwitters as an early reference, Twombly is affected by European modern art as an ideal of uncompromising self-expression, and a feel for the poetry in the most humble substances.

In 1950 he moves to New York and shares a studio with his new friend, Robert Rauschenberg. Together they enroll in Black Mountain College in North Carolina where their teachers are Robert Motherwell, Franz Kline and John Cage. In 1953, Rauschenberg and Twombly travel through Europe and North Africa absorbing, from the primitive to the sophisticated, the bases of western culture. Rome, the chic decaying city and its inhabitants will have a life changing effect on Twombly.

During the summer of 1957, while staying with Alvise and Betty di Robilant, the colors, the light, the heat, the food of Grottaferrata, liberate a libidinal fluidity of draftsmanship that find their best expression in a series of drawings done at night with the lights out. With Jean Dubuffet in mind we discover an esoteric elegance of deconstructed, dancing calligraphy.

Establishing a bridge between the US and Italy, Twombly will exhibit with Rauschenberg at the Stable Gallery in New York, and find early patrons in the Franchetti family in Rome. 1959 is a pivotal year, marrying Tatiana Franchetti in April in New York, moving to Rome in June, where their son, Cyrus Alessandro is born in December. From then on, a most prolific and glorious period of production begins, be it in photographs, sculpture or paintings.

“I sit for two or three hours and then in 15 minutes I can do a painting, but that’s part of it. You have to get ready and decide to jump up and do it; you build yourself up psychologically, and so painting has no time for brush. Brush is boring, you give it and all of a sudden it’s dry, you have to go. Before you cut the thought”

Vigorous yet ethereal Bach sonatas as played by Glenn Gould come to mind, when in 1961 Twombly; directly from oil paint tubes to canvas with his fingers and hands, produced “The Triumph of Galatea”. For Twombly, using his hands as the main instrument of picture making had a symbolic and pragmatic purpose. Attracted by the prehistoric, primal applications of paint by humankind (he had visited the Lascaux grottoes with Rauschenberg in 1952), it gave him a more physical, sensual approach to the canvas, rhythmically clawing, dabbing or caressing it.

With an uplifting, nervous and elegant choreography, Twombly mixes irregular motifs and organic movement, with intuitional and cerebral expression. The paintings of this era are perhaps a perfect example of what Twombly terms his “irresponsibility to gravity”

In December 1963, soon after the assassination of President Kennedy, Twombly created “Nine Discourses on Commodus“. With Francis Bacon in mind (a painter he much admired) we are ravished by a powerful ensemble of energetic emanations, “From cloud like lightness to agitated bloody violence – a reflection on leaders, disasters and the fate of empires” *2

More than any modern artist, Cy Twombly embodies Cennino Cennini‘s theory. The 14th century Florentine painter asked two of his students to draw an identical circle. Looking at the results, he found that even with the utmost care, no two circles could be exactly identical; because, Cennini concluded, the hand is lead not by the brain, but by the ‘anima’: the soul.

At the end of the 19th century, psychoanalysis developed the idea that our actions are the result of our conscious and the unconscious. Creativity is its proudest emanation. Balanced or unbalanced, artists are the luckiest humans. With their art they can express their inner soul, and we, bewitched, bothered, bewildered, nauseated or elevated, thank them for it.

Constantin Brancusi said ” it is not difficult to work; it is difficult to get in the mood to work” Twombly usually found inspiration during periods of parallel activity such as travel or extensive reading. Literature and poetry are a fundamental sparkle throughout the prolific, enlightened oeuvre given to us by Twombly’s generous soul.

Looking at art is primarily a physical experience. Books and computers cannot render scale, texture, depth or nuances of color. Nothing can replace the thrill of standing in front of a cherished image. The Twombly retrospective at Musée Pompidou in Paris is a beautiful and thorough exhibition that should not be missed.

*1 *2 Kirk Varnedoe, ‘Cy Twombly: A Retrospective’, MoMA, New York, 1994

Centre Pompidou, ‘Cy Twombly’, until April 24, 2017

All images © Cy Twombly Foundation

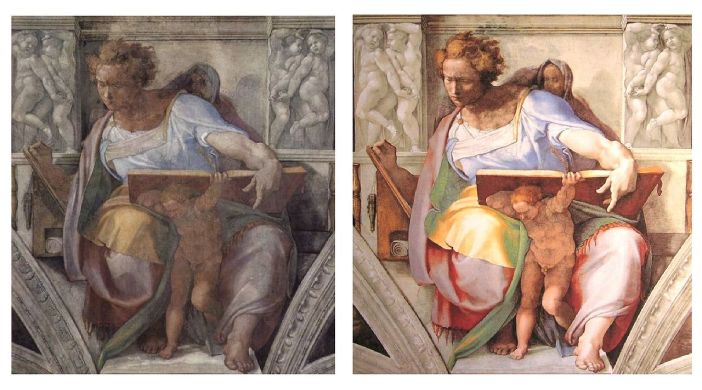

One of our Professors at University, Gianluigi Colalucci was head restorer for the Sistine chapel project. Close examination by his team revealed that apart from smoky deposits, seepage deposits and structural cracks; the thin “pictorial skin” of Michelangelo’s frescoes was in excellent condition. Most of the paint was well adhered and required little retouching. The plaster, or

One of our Professors at University, Gianluigi Colalucci was head restorer for the Sistine chapel project. Close examination by his team revealed that apart from smoky deposits, seepage deposits and structural cracks; the thin “pictorial skin” of Michelangelo’s frescoes was in excellent condition. Most of the paint was well adhered and required little retouching. The plaster, or